Nepal’s 2015 earthquake, the biggest in a hundred years, killed almost 10,000 people and destroyed countless old structures in the Kathmandu Valley—temples, palaces and shrines. It also damaged Kathmandu’s most famous historic library, located in a 130-year-old sprawling palace complex of several buildings, a large courtyard and stunning, verdant grounds, the Garden of Dreams.

“In the months following the disaster, we lost many idols from temples and shrines around the valley. And here in the library, many books were destroyed, and others disappeared. It was very sad. But now we are in the final phase of restoring the library building to its former state,” recounts Ankita Shrestha, who works on the extensive retrofitting of Kathmandu’s spectacular Kaiser Library while pursuing her master’s in urban planning.

Kaiser Mahal, the palace complex where the library is housed, sits in the heart of Kathmandu, a stone’s throw from the bustle of Thamel, the city’s prime tourist area. Constructed in 1895 by Field-Marshal Chandra Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana, who served as prime minister from 1901 to 1929, the main building is a neoclassical edifice that now stands amidst modern city blocks. Chandra Shumsher helped sign the 1923 Nepal-Britain Treaty, establishing the country as an independent state. The imposing three-story building has four wings, two of which house the library. Wooden stairways, long corridors with tall windows opening onto a tree-lined courtyard and high-ceilinged rooms project a regal air. The palace’s floors are crafted from thick Italian marble brought from Europe on horseback.

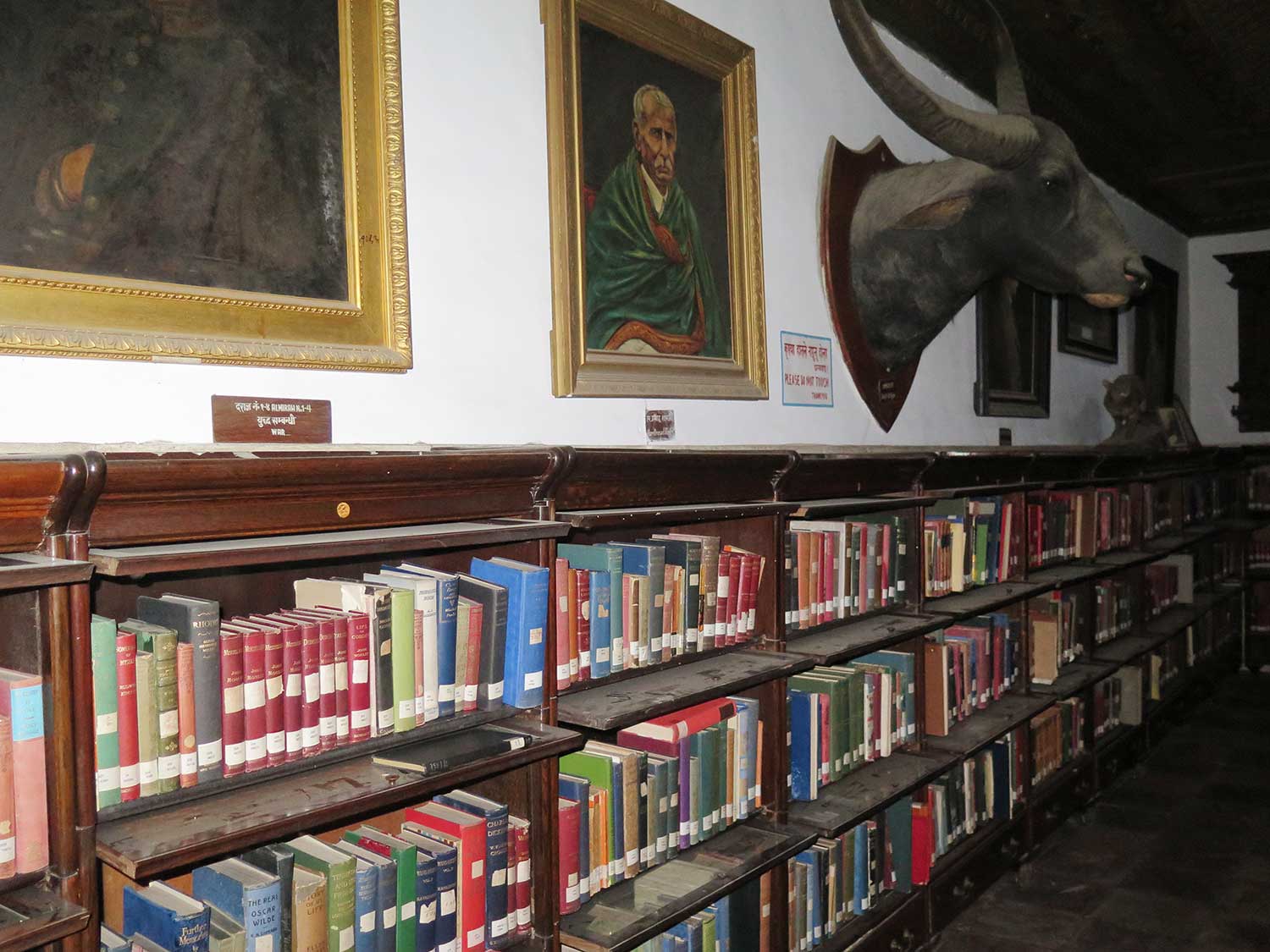

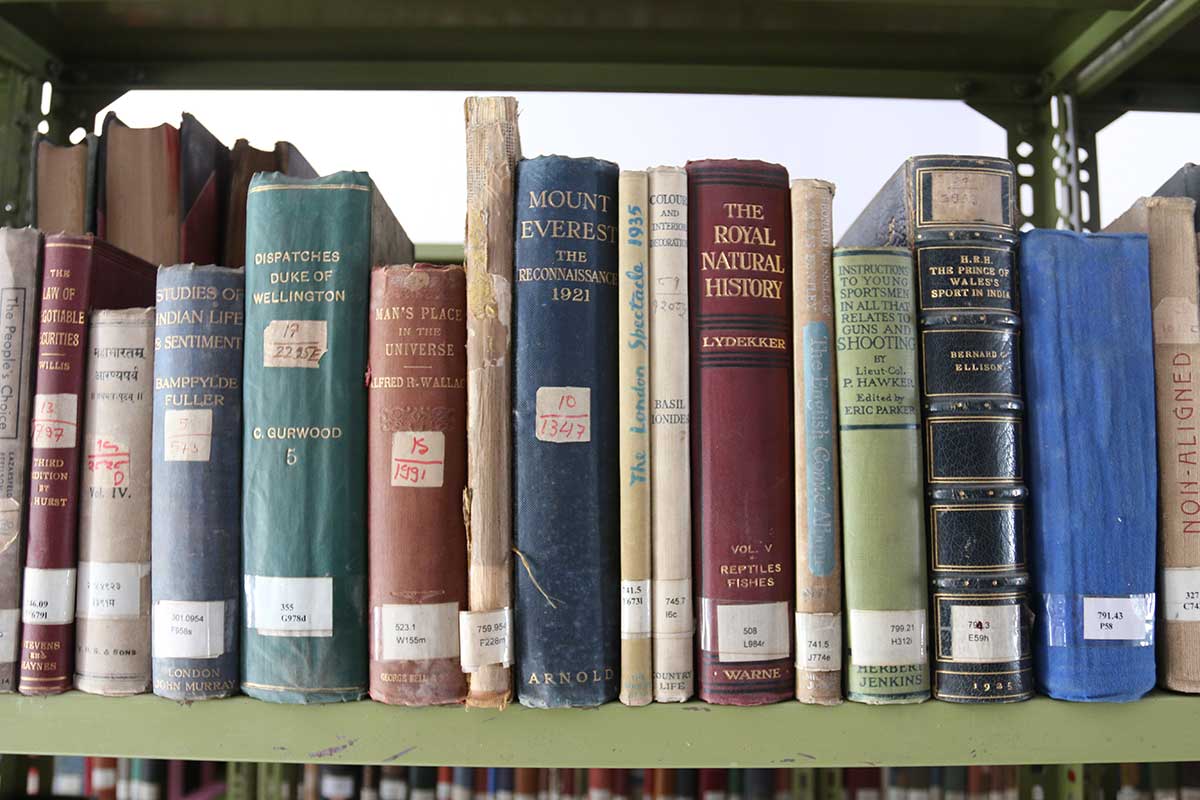

In 1908, Chandra Shumsher’s son, Kaiser Shamsher Jung Bahadur Rana, accompanied his father to London where he immersed himself in the British capital’s museums and libraries. This inspired the young man to start a private library in the family palace. He amassed thousands of books, antiques, animal trophies and paintings. In 1920, a so-called Garden of Dreams, an almost 7000 square meters neo-classical garden with several pavilions, an amphitheater, ponds, pergolas and statues, designed in Edwardian style by landscape architect Kishore Narshingh, was added.

The library was closed to the public until the death of Kaiser Shumer in 1964 when his family handed the entire complex over to the Nepali government. While the Garden of Dreams fell into neglect, the library, then holding some 60,000, mostly English language books, manuscripts, pamphlets and periodicals was managed by the Ministry of Education, which was also housed in the palace.

In 1998, the Garden of Dreams, by then seriously dilapidated, was to be demolished to make way for a shopping mall, but the Ministry of Education, in collaboration with Austrian Development Aid, restored the property and opened it to the public in 2007.

Rebuilt once again following the earthquake, the stunning garden now provides a rare respite from the traffic chaos of central Kathmandu and is an oasis of peace, both for locals and tourists. A chic café offers snacks, families pose for selfies and young lovers carve out moments of privacy on the many benches dotted around the compound.

The palace building has been restored to its former glory, with several additions.

“The roof had fallen in; some walls had collapsed. For a long while after the quake, the books remained in the partially collapsed building until a temporary structure was erected to rehouse them,” Shrestha recalls.

Reconstruction started in 2018. In Nepal, buildings older than 100 years cannot be renovated. Following strict conservation principles, they must be retrofitted. Traditional building techniques must be used in the reconstruction and maintenance of historic buildings.

“The entire retrofitting construction project was funded by the Nepali government. We could not follow all the rules because we had to strengthen the building to maintain its original state, but we followed traditional construction techniques as closely as possible,” Shrestha notes.

The library’s car park has given way to a new pavilion, designed by Australian architects, in keeping with the structures in the Garden of Dreams.

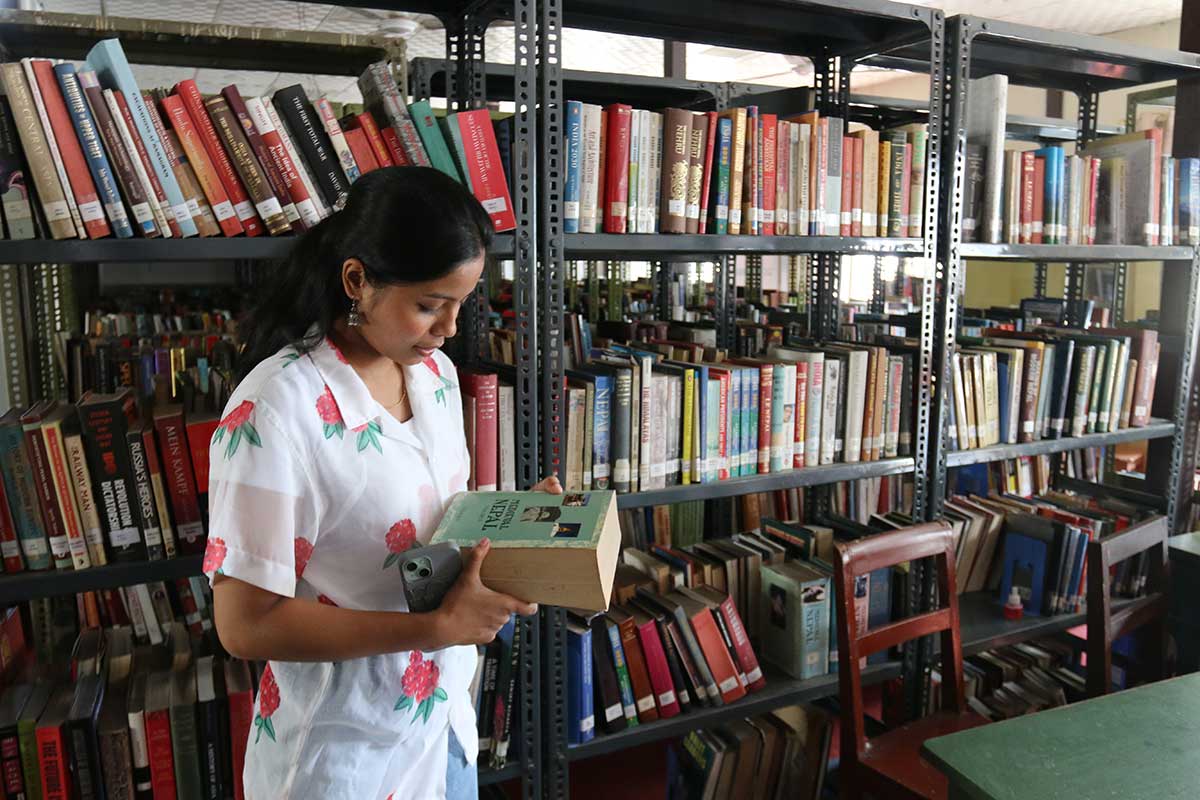

“We are now in the final phase of the project, putting in a false ceiling,” Shrestha explains, “The library is in the palace’s east and south wing, the rest is given over to government offices. Once the false ceiling is in place, the building will be handed over to the government. The children’s books have already shifted into the palace’s former dining hall. The books are being arranged room by room now.”

The building is already open to the public and students use the large courtyard to study and hang out. Some of the palace’s old furniture has been restored. The books have long been divided into several collections. A new book collection, amassed post-1970, is already accessible to the public in the temporary building. But the core Kaiser collection which contains 28,000 antiquarian, rare and beautiful books on a wide range of subjects including religion, philosophy, astronomy, hunting, medicine and literature, including first editions of Graham Greene’s early novels, countless colonial era British volumes and a beautiful, illustrated edition of Alice in Wonderland, remains locked away, along with hundreds of manuscripts bound in cloth.

Librarian Heeru Nepali says that visitor numbers have dropped since the earthquake. “The Kaiser collection is still locked up for security reasons. Before the earthquake, we had 50 foreign visitors a day. When the books have all shifted back in a few months, we expect visitor numbers to return to previous numbers.”

For now, the Kaiser Mahal’s main draw is the spectacular Garden of Dreams, which is popular with both locals and tourists and offers rare moments of respite in the heart of the bustling city.