Flames engulf the gangster’s chest. Beaming from the core of this inferno is a scowl: the hostile expression of a sharp-toothed, sword-wielding, lasso-toting deity. This is the Immovable One, the Unshakable One, the ferocious, feared, and worshipped Fudo Myoo.

He controls lightning, commands evil spirits, is served by dragons, and inspires Japan‘s most powerful organized crime group, the Yakuza, members of which commonly have him tattooed across their torsos. Yet this Buddhist deity promotes compassion, is admired by millions of ordinary Japanese people, and resides in Osaka‘s most popular tourist district.

A narrow canal drenched in neon signage and lined by restaurants and bars, Dotonbori is an icon of modern Osaka. Travelers flock there to pose for photos in front of the giant models of squids, blowfish, crabs, and sushi chefs used to draw attention to venues in this crowded neighborhood.

All this fuss covers Fudo Myoo as he hides in a back alley in the area. Wandering through this kitschy wonderland, I find myself in the contrastingly sober and serene environment of Hozenji Temple. Almost 400 years old, this beautiful Buddhist complex is dedicated to Fudo Myoo.

He’s sat beneath a red Noren curtain, and between two traditional Chochin lanterns, which bathe him in a gentle light.

The green moss that smothers this stone statue conceals Fudo Myoo’s famously menacing expression. That growth is the result of a popular custom. Buddhists travel from all over to pour water over this likeness. In the process, they pray for him to shield them from evil. That’s because he’s one of the Kings of Brightness. Also collectively called Myoo, these five deities fiercely guard the tenets of Buddhism, protecting the religion from corruption and keeping a rein on evil spirits.

They became part of Japan’s Buddhist faith in the ninth century after being introduced from China. Tourists with a keen eye will spot statues and paintings of the five Myoo all over Japan. They’re also commonly depicted as a group, featuring Aizen Myzoo, Gozanze Myoo, Daiitoku Myoo, Gundari Myoo, and—most important —Fudo Myoo.

He is revered for his ability to exploit potentially harmful motivations like fury and ambition, using them to prosper rather than self-destruct. This explains why he’s such a totem for Japanese gangsters. Restraint and prudence are crucial in the criminal world. A Yakuza must pick his moments, lest his nefarious career ignites like the deity inked on his torso. While the Japanese mafia is ruthless, they’re more discrete than many other organized crime units.

Australian biker gangs ride en masse on cacophonous hogs. Some US gangs drape themselves in conspicuous colors. Yakuza prefer to dress like businesspeople in tailored suits and shiny leather shoes. Their calling card is hidden beneath these reserved outfits.

“Pray for the health and safety of our family”.

Yakuza are renowned for their elaborate tattoos, which can extend across most of their torso, arms, and legs. If you’ve ever been asked to cover your body art while at a gym or swimming pool in Japan, this explains why. For generations in Japan, tattoos were mostly sported by Yakuza.

This body art was illegal in Japan for more than five decades up to the 1940s and was then restricted until 2020 when it finally became widely legal. Tattoos are still disconcerting for many ordinary Japanese people. Of course, you’re far less likely to cause concern if you have a small forearm tattoo of your child’s name than a giant chest depiction of a flaming deity.

Before the Yakuza emerged, Fudo Myoo inspired generations of a similarly fearsome but more upstanding class of men. He was revered by Japan’s famous Samurai. These gifted warriors had an enormous influence on Japanese society. They, too, admired Fudo Myoo’s capacity for constructively wielding his burning passion.

But his appeal is not limited to fighters and criminals. That becomes clear to me during my visit to Hozenji Temple, one of several Buddhist complexes across Japan dedicated to Fudo Myoo, including Tokyo’s Fukagawa Fudo-do and Takahata Fudo-son.

As I watch from a distance, Japanese people take turns praying before this deity. They burn incense or light candles inside the Toro stone lanterns alongside Fudo Myoo before bowing before him. Foreigners, too, request help from the King of Brightness.

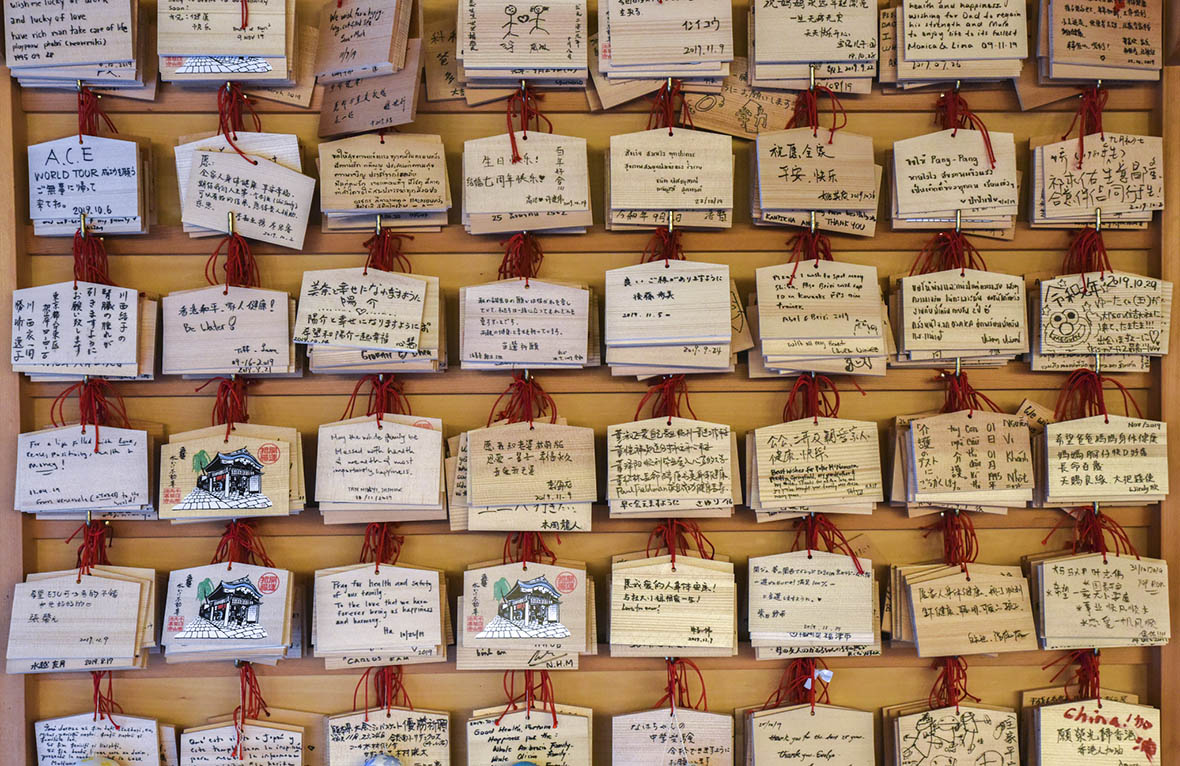

Near this mossy statue is a rack from which hang hundreds of Ema, small wooden plaques that for more than 1,000 years have been used to send human wishes to Japan’s Buddhist and Shinto deities.

Most are conveyed in Japanese. Some, however, are written in English, Spanish, Romanian, and Thai.

“Pray for the health and safety of our family,” reads one, signed by “Ha”. “To the love we have forever, bring us happiness and harmony”.

According to Japanese Buddhist belief, the messages left here at Hozenji Temple float into the sky and land in the lap of Fudo Myoo.

He may look daunting and be an idol for gangsters, but this deity promises to protect all who respect him: even tourists who never knew his name.