The common conception of a trip to Bhutan is a five-district circuit through Paro, Thimphu, Punakha, Gangtey and Bumthang. But on this, my second visit to Bhutan, I’m planning to focus on Paro. I’d stayed just one night here three years earlier and wanted to experience more of a town so often overshadowed by Thimphu, its larger, busier neighbor and capital of the kingdom.

Not only does the comparatively more rustic and real Paro offer plenty to do and see on its own, but I reckon this is my chance to spend more time getting to know one place, explore the surroundings, meet locals, and experience traditional Bhutanese healing techniques. I also want to delve deeper into Bhutanese cuisine.

On my first day in town, I learned to make ezay, the ubiquitous chili paste that accompanies every meal and almost every dish in Bhutan. Photographer David Van Driessche has taken me to Paro Penlop Penjor Dawa Heritage Farmhouse, a restored 18th-century residence built for a Paro governor who once ruled over nearly all of western Bhutan. His descendants still inhabit the house today, catering to locals and visitors who pay to view the old house and its antique contents, and to experience authentic Bhutanese cooking.

After climbing a well-worn wooden staircase as steep as a ladder to the upper floor, we’re invited into a rustic kitchen with an ancient-looking wood-fired mud stove. The patriarch of the family, a tall, sturdy man with close-cropped steel-grey hair and a warrior’s bearing, takes charge of the ezay. Squatting on the smooth wooden floor, he tosses a handful of roasted red chilies, along with garlic cloves, Sichuan pepper, tree tomato, ginger and salt into a large wooden mortar, and then mashes it all together in steady, patient strokes. He stops twice to sample a bit of the paste, and after correcting the balance of ingredients, he passes me a spoonful.

The ezay is so explosively tasty that I’d be happy to eat nothing else for the whole meal, but soon all the other dishes are ready, and we join the family on the floor to share the feast. We eat from thick wooden bowls, spooning food directly from iron cookware into the bowls, and then using small handfuls of steamed red rice to scoop the contents from bowl to mouth.

The star of the repast is shakam paa, a spicy hash of dried beef and daikon radish, redolent with roast chilies and long pepper. Kewa datshi, a hearty dish of sliced potatoes, Bhutanese cheese, and chilies, tastes like scalloped potatoes taken to the next level, especially washed down with jaju, a soup of milk, butter and turnip leaves. My tastebuds feel right at home.

Even for a long-time resident of Thailand accustomed to chili-forward intensity, the homemade ezay presents a bold entré into Paro food culture, and I’m hoping my long stay in Paro will likewise bring more impact and depth than the usual circuit route.

Of course, I’d be remiss in skipping the one place definitively on everyone’s bucket list. My humility and chi are both put to the test when I make the trek to 17th-century Paro Taktsang, or Tiger’s Nest, the revered Buddhist sanctuary precariously built over a cave where legend has it, Guru Padmasambhava meditated for three years during the 8th century. Near the trailhead, I catch a first glimpse of the mist-shrouded monastery clinging to the side of sheer rock cliffs and gasp at what appears to be a near-impossible climb. It is hanging almost a full kilometer above Paro Valley, and as my mind adds that to the four kilometers of ascending trails, I almost turn around and leave.

But it’s a perfect day of blue skies, drifting white clouds, and crisp mountain breezes. The trail, though difficult, is lined with fragrant blue pine, and scattered rows of yellow, orange and magenta wildflowers. The altitude makes hiking a slow march, but three hours later I’m walking barefoot inside hallowed chapels filled with bronze deities and incense smoke, alongside monks, local pilgrims and happy tourists.

If ever an accomplishment has earned me a beer, this is it. I head into town to visit Namgay Artisanal Brewery, which has only been open for five years and reflects the younger generation’s growing interest in global cultural trends. In a short time, Namgay has become the country’s premier craft brewery, and its adjacent spacious wood-and-stone brewpub, NAB Bistro, hosts live music from local bands with names like Crystal Dew Brothers, The Caterpillars, Baby Floyd, and Blue Phantoms

I met brewmaster Dorji Gyeltshen, who became acquainted with home brewing while studying hotel management in Switzerland. After graduation, he set up Namgay Heritage Hotel in Thimphu and ran it for five years, “because that was the deal I made with my father,” he says. “My dream was to build a brewery, but I only knew how to brew on a small scale. So, I invited someone from Brooklyn Brewery to stay in Paro for a few months and show me how to take production up to 2,000 liters per batch using bigger equipment.”

About 80% of the ingredients that go into Namgay beer are locally sourced, Dorji says. The water comes from a tributary of Paro Chhu. The base malts, hops, and yeast are imported for now, but Dorji will soon begin malting locally and hopes to work with local farmers to experiment with hops one day.

Today he’s producing six beers plus apple cider, of which I taste Red Rice Lager, Dark Ale, and Milk Stout. All three are tasty, but the smooth stout is my instant fave. While most of the fare in the brewpub is Europe- or India-inspired, a few Bhutanese dishes stand out, including hogay, a crunchy and spicy salad made of sliced cucumber mixed with chili flakes, tomato, cilantro, onions, Sichuan pepper and crumbled Bhutanese cheese. It goes very well with the Red Rice Lager.

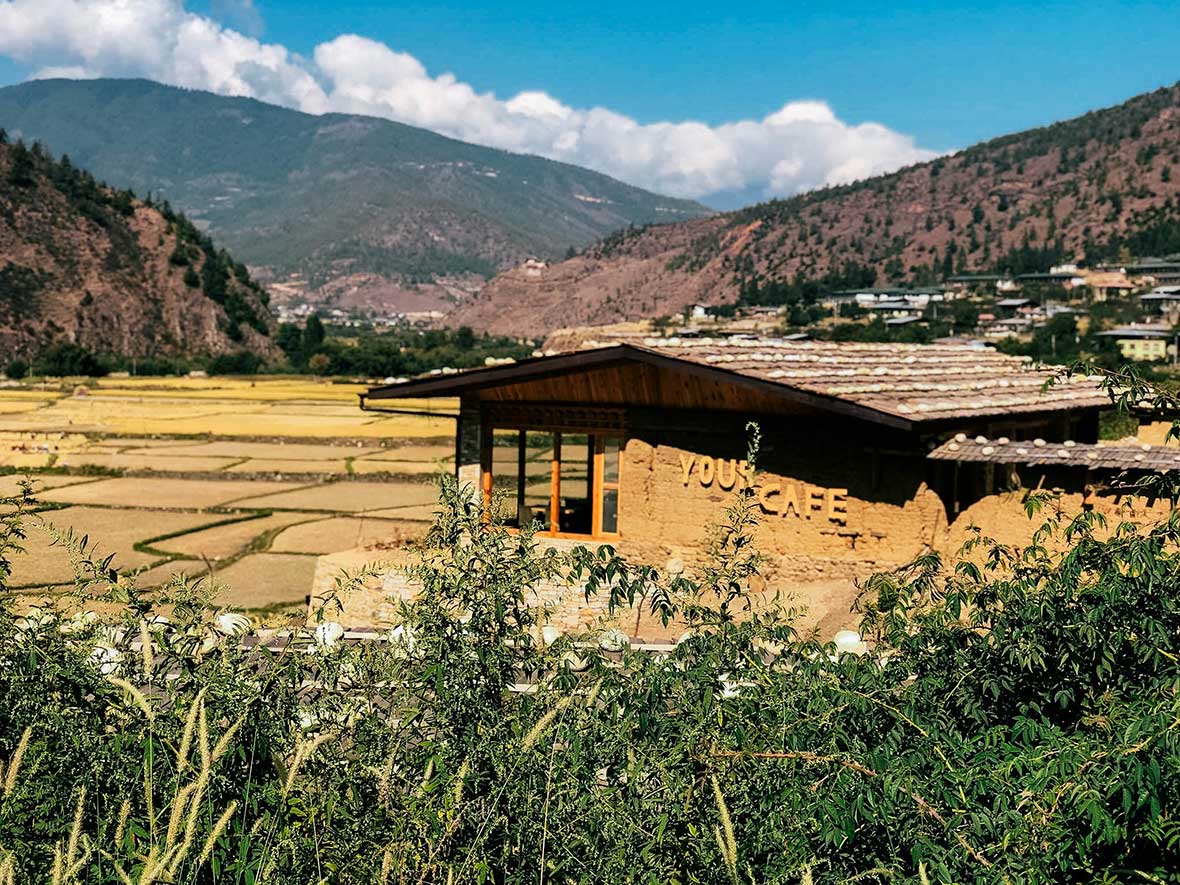

The following day I stop in at Your Café, annexed to a restored farmhouse dating to the 15th century in Shaba, for a perfectly made latte. The renovated mud-walled structures, called Neyphug Heritage collectively, include the café, a business center and shared workspace, an art gallery, and an outdoor farmers market. Conceived and overseen by Neyphug Tulku, the complex donates all proceeds to support the ongoing restoration of Neyphug Monastery, which was razed by a 2006 earthquake, and its monastic school. Serving a short menu of Thai, European and Bhutanese fare, it’s the only eatery in Paro that’s fully vegetarian.

The heart of the city is a matrix of narrow streets and older buildings decorated with hand-painted, pastel-hued Bhutanese Buddhist icons—treasure vase for longevity, parasol for wealth and protection, and lotus for enlightenment, among others—and ornately carved and painted eaves jutting from each floor. It’s easily navigated on foot or bicycle. Near the town’s main produce market, my gho-clad guide Sonam Tobgyal Dorji takes me through an unmarked door into Momo Corner, a local legend of Paro street food. The rustic dining room’s collection of padded benches and low tables is filled with locals.

Sonam orders, and soon we’re sharing plates of fresh-steamed momos, crescent-shaped ones containing minced beef, and round ones with chopped greens. Eying them for size, I reckon I’ll enjoy munching three or four but gorge on 10. Dunking them in the house ezay makes them especially more-ish, and I remember that for the last finished episode of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown, in which he ate his way across Bhutan, his first meal in-country was momos. “It’s enlightenment,” he gushed about what would remain his favorite dish. “It’s your third eye opening, man.”

Looking back on my week in Paro, I feel like all senses have been graced by bursts of enlightenment. From sinus-clearing ezay to the soul-cleansing goenpas, fortified by Dr Thinley’s herbal magic, I’m ready to descend from the Himalayas and take on urban life with renewed vigor.