Writing and drinking were in Graham Greene’s blood. Treasure Island author Robert Lewis Stephenson was his mother’s cousin, and the Greene King Brewery were also directly related. Greene boarded at Berkhamsted School, Hertfordshire, but life was never easy, and lapsed Catholic melancholy followed the writer like a storm-cloud most of his life. Prone to bouts of depression, soaring highs and crashing lows, school was a drag, but nonetheless he studied well enough to read history at Oxford before finding his feet as a journalist, first at the Nottingham Journal and later at The Times. The publication of his first novel, The Man Within, enabled Greene to quit The Times before drifting into espionage and the secret service while continuing to write both fiction and journalism.

By the early 1950s Greene traveled to Vietnam as a wide-eyed war correspondent.

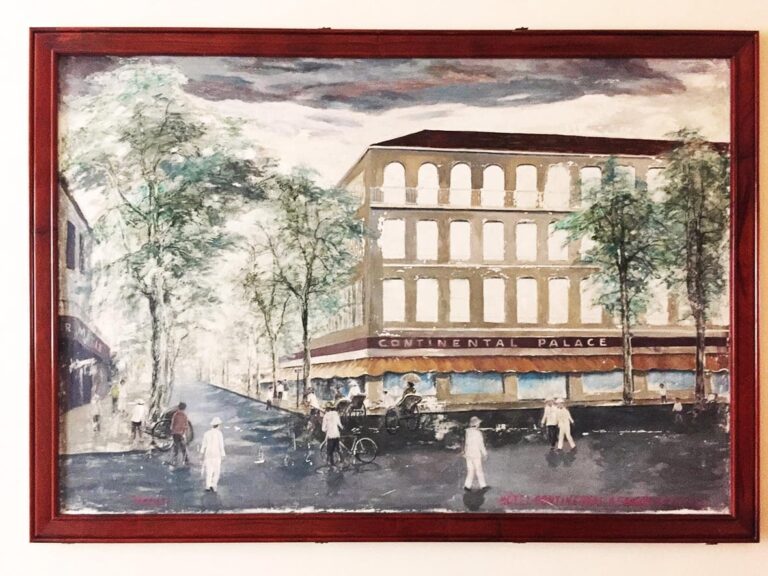

ABOVE: Hotel Continental in Saigon in 1968.

Prior to this Greene was well-traveled, having published his own travelogue – 1935’s Journey without Maps covering his 350-mile, 4-week walk across the Liberian interior. The Power and the Glory was written following Greene’s difficult relationship with Mexico.

Many of Graham Greene’s old Saigon haunts not only stand but have been restored to their original glory. What was once the Rue Catinat is now called Dong Khoi. The street stretches as far as the Saigon River, where river traffic still stirs much as it would have done in the 1950s. Cream-stucco haberdasher Catinat Fashions arrogantly stands with unshakable French colonial pride. Across the street the 1928-built Majestic Hotel that Greene preferred to the more journo-friendly Continental still stands. Francophile Greene would have no doubt enjoyed the colonial central courtyard and rooftop bar while contemplating the river traffic from above and afar.

ABOVE: Modern exterior of the luxury InterContinental in Saigon, blocks away from some of Graham Greene’s colonial haunts.

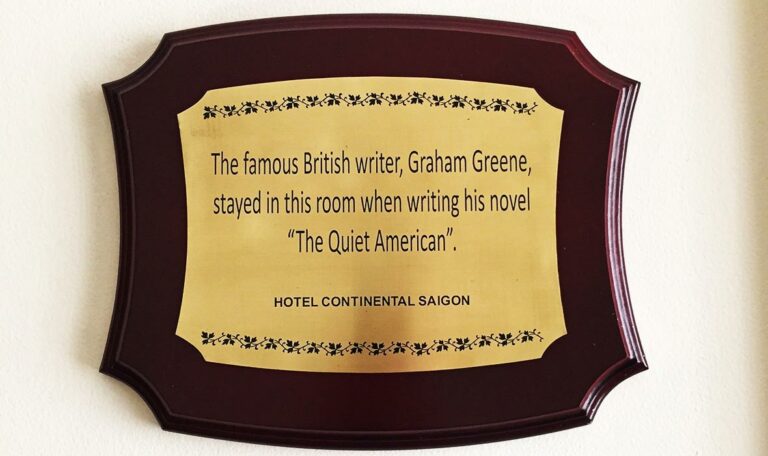

He’s well known at the Sofitel Metropole in Hanoi, with the famed Graham Green Suite and an eponymous cocktail, but he left his mark on the southern capital as well.

“I can’t say what made me fall in love with Vietnam – that a woman’s voice can drug you; that everything is so intense. The colors, the taste, even the rain. Nothing like the filthy rain in London. They say whatever you’re looking for, you will find here. They say you come to Vietnam and you understand a lot in a few minutes, but the rest has got to be lived. The smell: that’s the first thing that hits you, promising everything in exchange for your soul. And the heat. Your shirt is straightaway a rag. You can hardly remember your name, or what you came to escape from. But at night, there’s a breeze. The river is beautiful. You could be forgiven for thinking there was no war; that the gunshots were fireworks; that only pleasure matters. A pipe of opium, or the touch of a girl who might tell you she loves you,” reads the classic Graham Greene novel The Quiet American.

The model for the Quiet American’s protagonist Fowler’s apartment was probably a few doors down from the Majestic Hotel. A photo in Norman Sherry’s biography of the Life of Graham Greene shows the building in a dilapidated condition but now it’s looking much plusher as The Grand Hotel. Further up the street sits the Palais Café (the setting for another Quiet American scene) and further up still is number 109 Rue Catinat, another of Greene’s apartments.

ABOVE: The Grand Hotel, much reduced from its former glory.

A trip down Greene’s memory lane wouldn’t be complete without stopping at the lovingly restored Continental Hotel, a gathering place where correspondents and intelligence agents once mingled in the tropical twilight. The smoky atmosphere no doubt turned cynical after the third martini was drained and the chat turned political: semi-hushed conversations punctuated by loud raucous laughter. Silent American ghosts skulking in the hallways and scurrying up the stairs. Memories of the past blend with the present – the tourists here now are all well-healed, Japanese, European, golfing shirts and DSLRs, Lacoste tennis sneakers, and plenty of air miles.

Other Quiet American landmarks still exist. Letters can be posted from the central post office, the National Bank of Vietnam accepts deposits, and the cathedral remains in beautiful condition. The police headquarters building on 164 Dong Khoi (“dreary walls smelling of urine and injustice”) still stands. Back then political prisoners were tortured by electric shock before the building became headquarters for the government department of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

Despite restoration life has a habit of marching on and progress is inevitable. The Dakow Bridge where Pyle meets his murderous fate is being replaced. The House of 500 Girls, then known as The Parc au Buffles, is now an arts education center. The Opium Dens of Greene’s Vietnam dreamily evolved to a rolling skating rink and the brothels morphed into a ballet academy. Time marches on. Investment in arts and education has risen steadily as crime has fallen, and Greene would have trouble acclimatizing to the Vietnam of today.

Gone is the white-privileged, misguided bubble where diplomatic missionaries rubbed shoulders with international corporate spokesmen and talked shop with pinch-faced rubber baronesses. We can never return to those days, but why would we want to? Instead, let Greene guide you with his fiction, for novelists of Greene’s standing do one thing very well: encapsulate time, emotion, social, and cultural quirks. They paint cities, freeze them in time, for new generations to discover.

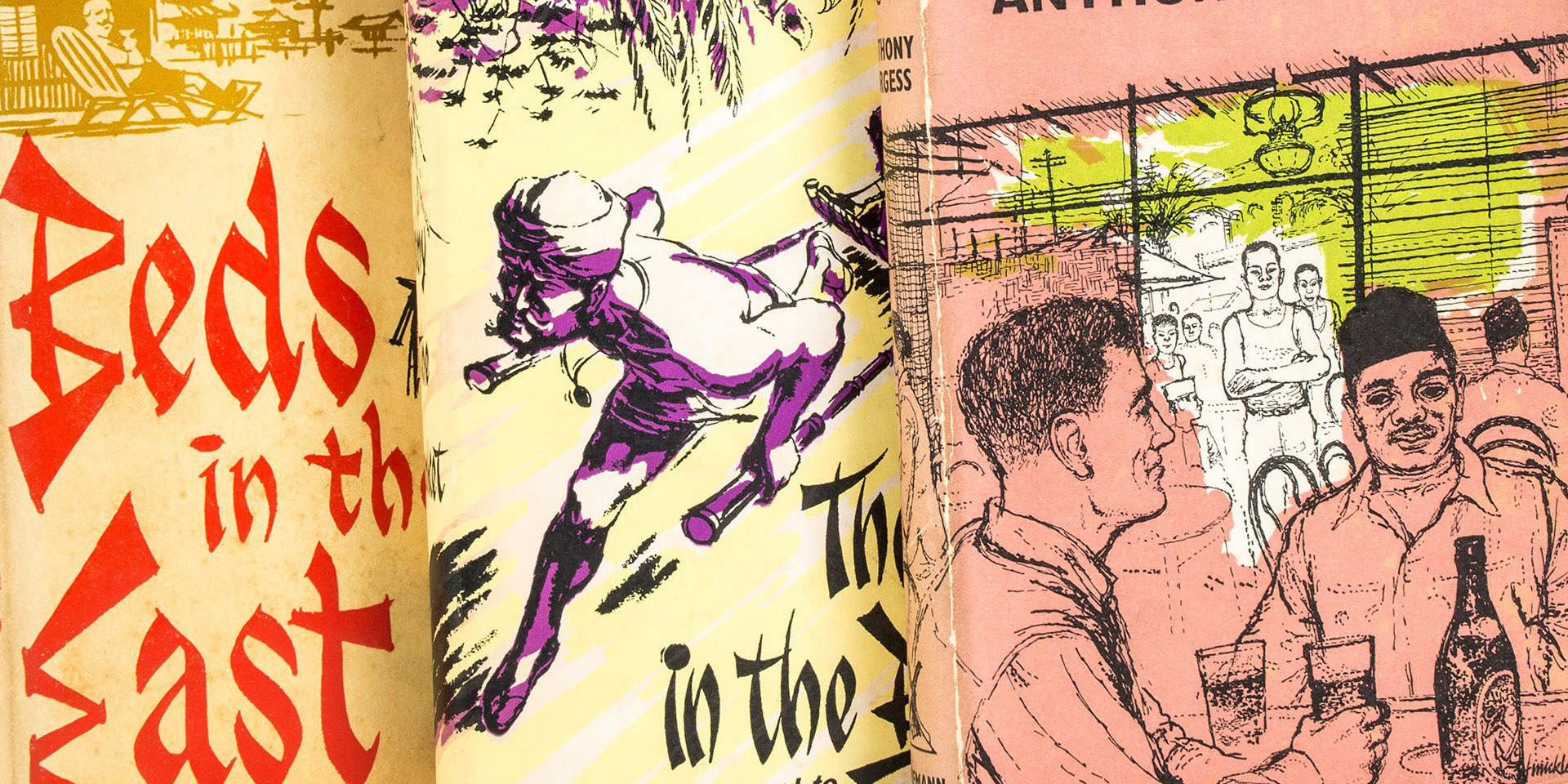

This piece is the second part of a series on famous expat novelists and writers living and working in Asia. For more, check out “Time for a Tiger: Anthony Burgess in Malaysia”. Photographs were provided by John Fengler and Staton Winter.